With the caveat that you are someone who is curious about the world and impatient to understand it. Math is the framework of reality. People usually talk about that in an abstract sense. I mean it in a more literal way. At some point the rubber meets the road and arithmetic is required. The easiest and most convenient way to answer small practical problems is with your own scientific calculator.

"Just use your phone"

If you don't have the $10-$20 for a nice calculator then yes. Use your phone. There are even cycle-perfect emulators of long-discontinued classic calculators. But a real calculator has many advantages.

- Tactile feedback. It is pretty nice to have actual buttons that actually depress when hit.

- Great battery life. Calculators typically have battery life measured in years instead of days.

- No games or distractions. Maybe this is just me. But a dedicated calculator is a tool for work.

- Never inappropriate. There are places where you should not use a phone.

- Always more professional. Using good tools shows you take your work seriously.

- Far more inexpensive and sturdy.

- Sometimes more powerful. (Though the best emulators will be just as capable.)

Do you ever carry a flashlight or notebook or wristwatch? If you do then you already get it. A dedicated physical thing is just sometimes more suitable than a digital jack of all trades.

I will admit that there is a problem with scientific calculators: most aren't made for professionals. They are made for students. The educational market dwarfs the professional market. Ultimately the student has a singular purpose for the calculator: passing a test. Schools and institutions ban any calculators that are too powerful. Cross over that line and suddenly 95% of the market won't buy it. As a result many of today's calculators (while inexpensive and very fast) are relatively hobbled in some respects.

I can guess what you are thinking. "Graphing calculators have no such limits so if you want the best calculator use them." And you are correct. Graphing calculators have dizzying capabilities now. Everything from color touch screens to symbolic computer algebra systems. But outside of a classroom my graphing calculators just don't get used. I've had several and they were all very impressive. However they've all collected dust in a professional setting. The much less impressive scientific calculators were used every day instead.

In hindsight I can see why.

- Size and weight. The graphing calculators are easily 3x larger and heavier. They would be left behind at the desk. But also at the desk would be a computer. The computer is far more convenient than the graphing calculator. So in the field I'd carry a scientific and in the office I'd use a computer.

- Cost. At $10-$30 a scientific calculator is easily 5x cheaper. As a professional I could certainly afford the $150 calculators. But they are just as likely to break and more likely to walk away. I'd rather replace a $30 calculator.

- Battery life. A graphing calculator consumes 500x more power than a scientific calculator. This translates into a battery life of months versus years. Many scientific calculators have a solar cell and will continue to work without any battery at all.

- Ease of use. Graphing calculators are a usability nightmare. The majority of the functions are hidden behind menus. On a scientific (nearly) everything is out in the open. How do you do something? Press the clearly labeled button for it. Simpler calculators can be operated faster and with less errors.

That said.... if after reading this you still want a graphing calculator then my recommendation would be the $60 Casio FX-9750GIII. It is the least expensive model available that can run a Computer Algebra System and has a pretty fast Python environment too. I'll sprinkle some information about it throughout the review when it is interesting.

Who is making good scientific calculators now?

Generally speaking there are a couple of name brands that you can't go wrong with:

I highly recommend getting a name brand scientific calculator. They are already inexpensive and undercutting that price requires big sacrifices to quality.

Maybe you only want to upgrade your basic 4 function calculator for something with more oomph. In that case there are a couple of options under $10 that are small/sturdy/reliable. One model stands out: the Casio fx-260 Solar II. It is the smallest scientific on the market that is respectable. It is the only model that I've seen that can easily fit in a breast pocket. And it is 100% solar with no battery. It will happily operate on 15 lux of illumination. (There is a purchase link at the bottom of the page.)

On the other hand maybe you want the best scientific calculator.... after all the top-shelf name brand calculators are only $20-$30.

What capabilities do you get with the fanciest modern scientific calculators?

- A general purpose equation solver that can handle any algebra or trigonometry.

- The ability to program formulas and batch-process data.

- Create trend line equations from real-world measurements.

- Solvers for polynomials and systems of linear equations.

- Definite integrals and derivatives. (Sometimes these work inside the solver too!)

- Tools for calculating probabilities: permutations, combinations, distribution functions.

- Tools for working with small matrices.

A little disclaimer: these aren't actually modern. All of these features have been available in $20 calculators since 2000. However nearly everyone I've talked to was completely unaware of these features. Some even had a calculator with these capabilities but didn't realize what they could do. I think this comes down to 2 things: schools buy the cheapest calculators for their students. The low-end scientifics don't have these really amazing features so it isn't discussed in the classroom. The students who bought their own calculator either never read the instruction manual or didn't yet have the mathematical background to understand the capabilities.

The Best (is really tricky)

Unfortunately there is no clear winner here. There are 2 very strong front-runners: the Casio fx-991Ex Classwiz and the TI-30X Pro MathPrint. They are very nearly equivalent except for the following 10000 words describing the minor differences between them. Don't expect this review to be as good as Jim Cullen's shootout between the Casio fx-115ES and Sharp EL-W516 but that is the level I'd like to strive for.

For the sake of brevity I will often refer to these calculators as either "Casio" or "TI." On a few occasions I will be referencing the company instead of the calculator but those should be obvious from context.

Handy background information:

- Casio's fx-991Ex Classwiz product page

- Casio's fx-991Ex Classwiz PDF manual

- TI's TI-30X Pro MP product page (german)

- TI's TI-30X Pro MP PDF manual (UK)

- fx-991Ex Classwiz in the calculator.org database

- TI-30X Pro MP in the Datamath database

- fx-991Ex Classwiz review by Numericana

A calculated conspiracy?

Americans might be scratching their head about my choice for TI. You've probably never heard of it. Texas Instruments wants to keep the TI-30X Pro MathPrint a secret in order to sell you an older calculator instead. They won't even publish an english webpage for the UK audience in case an american might read it. (Its in a photo there. But no webpage.) Instead the calculator quietly is for sale in European shops. Why did this happen? The previous generation of calculator that it replaced was a major embarrassment. Shortly after releasing the 2010 TI-30X Pro MultiView it was found to have a serious bug. It was pulled from shelves and delayed by almost a year while those were fixed. In 2011 it was re-released under the same name in europe and brought into the US as the TI-36X Pro which americans may be familiar with. However the calculator was too powerful for some german classrooms. In 2015 TI stripped out those features and released the TI-30X Plus MultiView. But then in 2017 some clever students figured out that a couple of keypresses would unlock the stripped-down Plus into a full-featured Pro. Oops.

Besides those showstopping problems the calculator had some "harmless" but still embarrassing issues. For example it provides 2 different input methods: a graphical "mathview" mode and a textual "classic" mode. The classic mode does math 2x faster. This bug carried into the TI-36X Pro. Whoops.

Texas Instruments had already made 2 major firmware rewrites for this calculator. Someone made the call to avoid a 3rd rewrite (along with a new body or color to make the old cheater's version obvious) and instead release a new calculator. I highly doubt that TI designed this new calculator in 1 year. It seems more likely that they had the design ready and waiting for when the market demanded a new calculator. So in 2018 they came out with the TI-30X Pro/Plus MathPrint. 8 years was a good run for the previous generation.

Now over in America we've had the TI-36X Pro since 2011. But like their graphing calculators TI seems wants to milk the old model for all that it is worth. 11 years now and counting. Who knows when we'll see an update? But we know what the update will be - it's already in Europe. Or maybe we never will. The new calculator is powerful enough that it handles much of what a graphing calculator can do and TI wouldn't want to cut into their most lucrative segment.

This follows a general trend of neglect by TI for scientific calculators. The last really nice scientific calculator from TI was the TI-68. It was in production from 1989 to 1999. At launch it wasn't a cheap calculator: $150 in today's money. Even when it was discontinued it was still $65 with inflation. But wow the things it could do. It could solve quartic polynomials. It could solve 5th order systems of linear equations. Complex numbers were fully supported by every function. It could integrate over any variable of equations stored in a continuous memory function library. After that every scientific from TI was weaker. Texas Instruments also sold calculators with a numerical error bug for 24 years. It wouldn't be until 2011 that TI finally added a new feature to their scientific calculators: a general purpose equation solver was introduced in the previously mentioned 2011 TI-30X/TI-36X Pro MV. (And that solver has had an embarrassing bug remain unfixed for 11 years and counting.) TI has an uphill struggle of embarrassing issues. Its almost as if they lost an entire generation of engineering and design experience. Meanwhile Casio was continuously improving their calculators and it shows in a lot of the little details.

Quick overview of the Casio fx-991Ex ClassWiz (2015)

- It is FAST. Easily 10x faster than the pioneering models from 2000 if you are thinking of upgrading. It can integrate faster than many graphing calculators. The CPU is 37% faster than the rival TI-30X Pro MP.

- It is powerful. It can solve quartic (4th order) polynomials. Quartic inequalities. Linear systems of 4 variables. And it can do math on 4x4 matrices.

- Impressive gimmicks. There is a spreadsheet that can use any of the calculator's functions. (Excel can't do integrals. This can.) Anything on the calculator can be exported via QR codes.

- Its got polish. The physical design and power efficiency is great. Casio has never held back from making the best calculators they could. Entering and editing long functions is a breeze.

- 9 regional versions localized for different languages: english, japanese, german, czech, slovakian, polish, hungarian, chinese, arabic, french, spanish, catalan, basque, portuguese

It does have flaws however.

- Routinely forgets everything. Wiping the memory across a power cycle is understandable but changing modes will erase all your work.

- Do not buy if you are color blind!

- Missing some "simple" functions that lesser Casios have. (GCD, LCM, remainders)

- Over-use of pictograms in the menu. Base-N/matrix/stats/distribution/spreadsheet/table can be easily confused at a glance.

- 9 regional versions each with different features. The US and DE versions can do calculus in the solver. The JP and CE versions have a periodic table. The DE and JP and SP versions can do product series. Nothing has everything.

Quick overview of the Texas Instruments TI-30X Pro MathPrint (2018)

- It is pretty fast. 2x faster than the TI-36X Pro.

- Often returns answers quicker than the fx-991Ex.

- Continuous memory! Everything is saved when the calculator is off.

- Really good regressions and distributions. Astoundingly well thought out.

- Supports complex/matrices/vectors/base-n in the main editing space.

- Function memory to hold 2 functions.

- Crude spreadsheet-like functionality using 3 lists. (This is a new feature not present in the TI-36X Pro.)

- Less restricted integrator and solver than the fx-991Ex.

- Menus are nicer and show their options up front.

- Constants give both their full name and their units.

- Clean and professional appearance.

- The cover can double as a surprisingly good notepad.

And its flaws:

- Europe only! Americans must import it.

- It is faster than the fx-991Ex because of lower numerical precision.

- Each variable requires up to 8 keypresses to enter.

- Expression programming is weak.

- Solver can't entirely be trusted.

- Inconsistent UI and a few nearly useless buttons.

- Typical 3rd order tools.

- Very power hungry for a scientific calculator.

Detailed comparisons

The little things

TI included a full assortment of "trivial" numerical functions that Casio lacks. LCD, GCM, integer part, fractional part, modulus, minimum, maximum. These are pretty interesting because they can be used in expressions and allow for creating arbitrary piecewise functions. Normally conditionals would be required for that. Unfortunately the weak expression evaluator and tedious solver hobbles much of the potential.

The fx-991Ex lacks a product (∏) series. (The english localization at least.) However I don't consider this to be a major issue. Instead use e^sum(ln(x)) since adding logs is the same as multiplying numbers.

Casio has a dedicated button for shifting the exponent by 3. This sounds trivial but it is nice when using the engineering display modes. The TI-30X Pro has no way of doing this.

Pretty much all calculators have a dirty secret (PDF) and the fx-991Ex performs identically to the TI graphing calculators. It will round off 1E-13. However TI's scientific calculators must not be as good as their graphing calculators. The TI-30X Pro rounds off at 1E-12 instead. This lower precision results in a speed boost for benchmarks.

Using variables is far nicer on the Casio. Both calculators allow you to use the 'x' variable with a single keystroke. However TI has every variable bound to 1 button that you tap repeatedly up to 8 times. Casio instead uses the traditional 'alpha' modifier. Maybe you might prefer to use the "recall" menu to access variables. Casio's recall menu is excellent. All 9 variables can be shown on the screen at once. You press the letter (without the alpha modifier) and the variable name is inserted to the expression. The TI-30X Pro's bulkier font means only 3 variables may be displayed. You then need to scroll down (same number of button presses as the multi-tap key) or simply type the number of button presses. However this is confusing because you can't see the number:variable shortcut mapping for anything below the fold. The TI-30X Pro then inserts the actual value of the variable into the expression. This clutters up the display and makes it so you can't know where a value came from. Updating a variable and re-running old expressions of course not possible.

TI confuses things further by placing the hex entry keys on the number keypad. These can't be used for variable entry or selection. So to get the 'a' variable you may either press the variable button 5 times or "recall down down down down enter" (pressing right or left jumps you back to the top of the list) or "recall 5." However the "5" key is clearly labeled E. Entering A (the hex value 10) does nothing by itself. (It could be a shortcut to a variable.) Instead the hex value must be followed by "2nd base-n right 1" to append the "h" hexadecimal unit. To rub salt in this TI started the hex letters on 1 instead of 0. This makes all the hex values appear to be off by 1. To enter a D (13) you press "4" instead of 3.

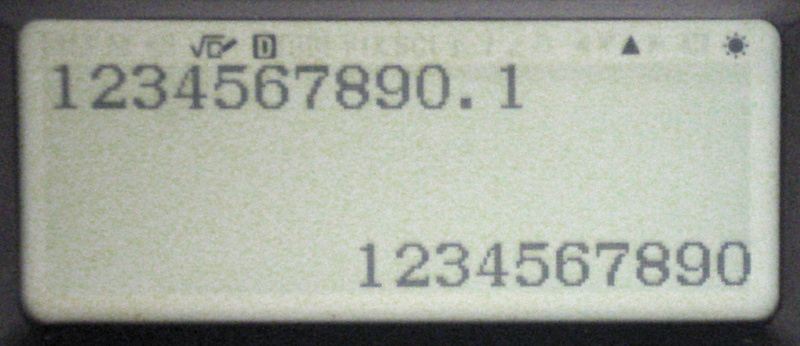

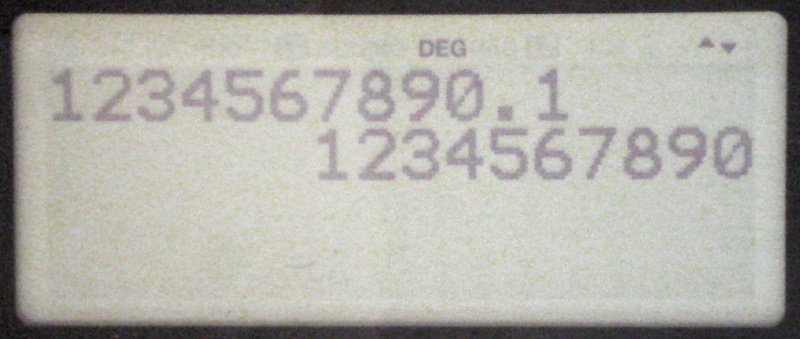

People have complained the TI-30X Pro can only display 10 digits. But the fx-991Ex has the exact same issue. In fact every scientific calculator I have ever owned does this. I don't feel this is a deal breaker because 10 digits is the defacto standard and engineering generally doesn't require that level of precision.

The fx-991Ex allows you to enter much longer expressions. Entering "1+1+1+..." on the fx-991Ex runs out of space at 199 characters (a sum of 100). The TI-30X Pro runs out at 101 characters (a sum of 51). In practice this is plenty for each calculator due to other design choices. Both good and bad.

The TI limits the level of nesting inside the graphical MathPrint mode to 4 levels. The fx-991Ex allows 13. In part this is because of Casio's more compact font but it does get weird on the Casio in the extreme cases.

Both can generate random numbers but TI gives 9 decimal digits while Casio only gives 3. The same RNG they've been using since at least 1980. It feels very archaic. Both can do random inclusive integer ranges.

Benchmarks

Nearly every forum post and comparison makes the claim that the TI-30X Pro MP is faster than the fx-991Ex. I don't agree. The TI returns (some) answers earlier but the Casio is clocked faster. How is this possible? TI keeps track of less digits and that provides a small boost. The biggest shortcut comes from decreasing the scope of the integrator. Since many community benchmarks are integration tests this makes the TI appear to be faster.

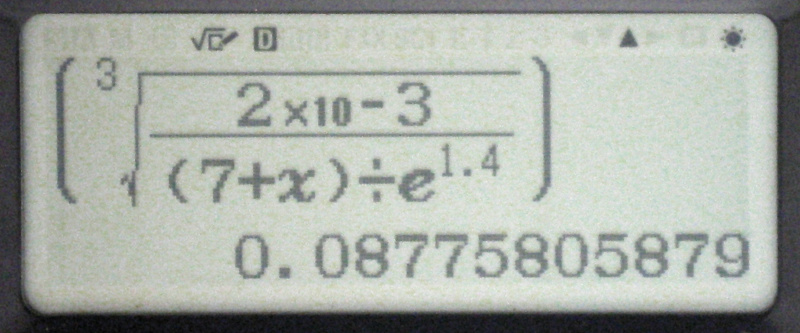

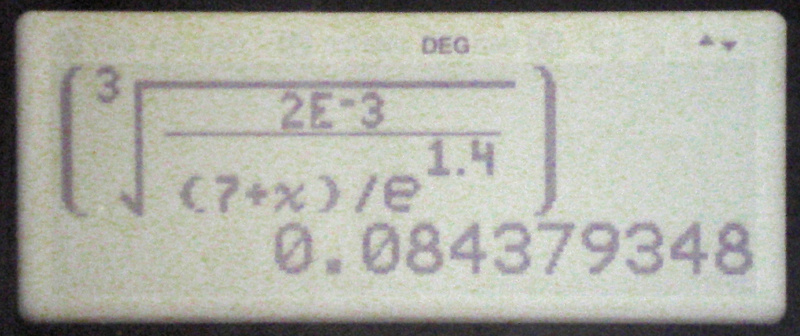

These calculators are very simple devices. The do not contain any sort of coprocessors or acceleration or even an FPU. Everything is done by a single small microcontroller. Because of that a very simple benchmark can actually be pretty fair. The simplest benchmark is to sum up a lot of integers:

| TI-30X Pro MP | fx-991Ex | fx-9750GIII | |

|---|---|---|---|

| sum(x, 1, 1E4) | 27 seconds | 17 seconds | 11 seconds |

Of course there can be algorithmic differences for a benchmark this simple. I had found something unexpected when digging through Casio's manual for details on the integrator. They claim that summation also uses the Gauss-Kronrod algorithm and potentially isn't just looping over numbers to add them up. It does make some sense because summation can be considered a "discrete integral" but it seems odd. Gauss-Kronrod is only supposed to help for continuous functions and a discrete series is anything but. Furthermore there are no speedups when summing a simple predictable continuous series:

| sum(1, 1, 1E3) | sum(1, 1, 1E4) | sum(1, 1, 1E5) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| fx-991Ex | 1.7 seconds | 16.7 seconds | 165 seconds |

So it seems the fx-991Ex is really just adding up all the numbers and it is a fair test between these calculators.

However most of the typical benchmarks are "comprehensive" benchmarks that involve many different types of calculation. In some sense these are more useful. A calculator is made for calculating so benchmarks should have lots of calculation. In other ways they are not fair. Calculators that use less digits or use sloppy approximations will appear faster than more accurate calculators. The most popular benchmark is a comprehensive test. Both of these calculators were already tested in that thread but nothing is wrong with experiment replication. In fact here is a head to head of both calculators and the American TI-36X Pro too. Let's rerun some of those tests. And just for fun I'll include times for an ancient Casio fx-991MS. (It uses Simpson's rule with 512 intervals.)

| test | TI-30X Pro MP | fx-991Ex | fx-991MS | fx-9750GIII |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sum((e^sin(atan(x)))^(1/3), 1, 1000) | 105 seconds | 102 seconds | n/a | 25 seconds |

| sum(x^-2, 1, 500) | 23 seconds | 23 seconds | n/a | 3 seconds |

| int(e^-x, 0, 100) | 2.7 seconds | 3.5 seconds | 108 seconds | 0.8 seconds |

| int(e^x^3, 0, 6) | 9.0 seconds | 25.4 seconds | 134 seconds | 4.4 seconds |

The TI does appear substantially faster when integrating exponential curves. However there is more going on here. At the beginning of this review I had mentioned Jim Cullens's thorough calculator comparison. He did a similar test on the venerable Casio fx-115ES. Page 75 talks about integrating the Standard Normal Deviation. The fx-991Ex gives the exact same answer of 0.682689492136081 including hidden digits. (The final digit of the 15 digits is incorrect.) Casio's integrator appears unchanged since then 2005. But thanks to Moore's law it only takes 0.8 seconds instead of 4.5 seconds.

The TI on the other hand does poorly. At 1.6 seconds its quick but not as quick as the Casio. The full result with hidden digits is 0.6826894921373. Not only is it 2x slower and 4 digits less but the last 2 digits are wrong!

Even simple derivatives have this problem. On pg 77 Jim Cullens tests d/dx ln(x) at x=e. The Casio returns a 15 digit result (with hidden digits) that is correct to 10 digits. 11 if rounding. On the other hand TI only computes 8 digits with no hidden digits. The result is only accurate to 7 digits. The 8th is so wrong that its not even saved by rounding.

It isn't clear which calculator has better trig functions. Casio usually is more accurate but sometimes TI is closer.

| test | TI-30X Pro MP | fx-991Ex |

|---|---|---|

| int(sin(x), 0, 2pi100) | -3E9 | -2.67E-11 |

| tan(pi/2 - 1E-9) | 1000103391 | 1000000000 |

| tan(355/226) | off by 0.015 | off by 0.26 |

Any claims that this TI is faster than the Casio must be taken with a grain of salt. TI might cross the line before Casio but they are cutting corners and are wrong 3 or 4 digits earlier.

Data types

There is a big philosophical difference between the calculators here. I generally favor TI's philosophy though the implementation is weak in places.

Casio uses different modes for accessing the data types. Want complex numbers? Change to complex mode. Want hexadecimal? Change to base-n mode. Each mode has a streamlined UI so that you only have to deal with the appropriate menus and sometimes changes the keypad around for more convenience. However this means that you can't do trig in base-n mode. Or shift the exponent in complex mode. And every mode change wipes the memory.

TI instead lets you use most data types in the main environment. Base-n/complex/vectors/matrices are not unique modes and are always accessible. (Lists are an exception. They have a dedicated UI.) Though it isn't fun entering hex on the TI-30X Pro and requires a lot of keystrokes. The fx-991Ex allows you to enter an N digit hex number with N keystrokes. The TI-30X Pro needs (up to) 2N+4 keystrokes.

Unfortunately the support for complex numbers is shallow in both calculators. You may only do simple arithmetic on complex numbers. They can't be used in vectors or the solver. e^(pi i) is an error instead of -1.

Both can do 2-vectors and 3-vectors. Casio can do 4x4 matrices and TI does 3x3. Both use the convention of only doing arithmetic on variables that hold a matrix or vector. (You can't enter a one-off into the main environment.) Surprisingly the fx-991Ex will remember those matrices (or vectors) across a power cycle. Of course they are wiped on a mode change. As expected the TI-30X Pro's continuous memory applies to the matrices/vectors too.

Vectors and matrices must be filled with real numbers. Neither variables nor complex numbers can be used with either calculator.

TI puts more matrix and vector operations into menus. Casio puts some operations onto keystrokes: cross product is multiplication and vector length is abs(). Casio has some extra vector operations: angle between 2 vectors and normalize to the unit length. TI has some extra matrix operations: inverse, row echelon form, reduced row echelon form.

The TI-30X Pro has 2 function memories (f and g) which can contain an arbitrary function. They may contain nearly anything. It is very common to set g = derivative(f) for various purposes. You may even set f = rand and hilarity ensues. These function memories also provide a way of working around the expression length limit.

Both support the antiquated degrees-minutes-seconds (DMS) format. Why is this even worth commenting on? It is a great shortcut for hours-minutes-seconds time entry! Casio's has a dedicated button and is faster to use. Only 3 keystrokes total. TI buries it in a menu and that means entering a full DMS number takes 12 to 15 keystrokes. Casio's is a little confusing because it displays the same degree symbol for each component as it is entered (1°2°3°) but then converts it to 1°2'3" when displaying results. Pressing the S<>D button then converts it to a decimal or a fraction. TI makes you enter the angle using distinct symbols for each component (less confusing) but then converts it to a decimal. Sometimes (but not always) you may convert it to a fraction with the <> key. TI will additionally convert it radians if you are in radians mode. Casio won't. TI's behavior of converting to decimals and possibly radians makes it useless for H:M:S entry. TI's system is so terrible that it is faster to enter a DMS number as "D + M/60 + S/60^2" (9 keystrokes) and won't convert to radians. Casio is the clear winner here.

The general purpose solver

This is the killer feature of these calculators. Type up an equation. Plug in most of the variables. It will solve for the remaining variable. No knowledge of algebra needed. The fx-991Ex and TI-30X Pro MP both allow for integrals and derivatives in the solver so it can do many practical problems involving calculus. Even as someone who is mathematically competent this is probably my most used and favorite feature.

This isn't the place for an instruction manual but I feel an example is needed to show how powerful and useful the solver is. Consider the family of problems that use exponential growth or decay. They appear in biological systems. In finances it takes the form of compounding interest or depreciation. Newton's Law of Cooling is exponential. And in chemistry when discussing radioactive decay. Let's say we have 60 grams of a radioisotope. After 1 year there are 50 grams remaining. How much is left after 10 years? What is the half life? The general form of the equation looks like y = x b^t and that is what would be entered into the solver. Then the solver will ask for the known values. In this case we know everything except for b so that is what we solve for.

| variable | y | x | b | t |

| description | final amount | starting amount | coefficient | time |

| value | 50 | 60 | ? | 1 |

The solver returns b = 0.83333 which intuitively checks out. If it was over 1 then it would be growth instead of decay. Next we want to find the amount left after 10 years. The initial reaction might be to look back to y = x b^t and manually plug 60*0.83333^10 into the calculator. But instead it is easier to stay in the solver. Simply change t to 10 and solve for y. The equation and all the other variables can be seamlessly reused without retyping anything.

| variable | y | x | b | t |

| value | ? | 60 | 0.83333 | 10 |

Solving for y gives 9.69 grams. Finally the half life. It starts with 60 grams so the half life will be reached at 30 grams. Solving for t under those conditions will find the half life.

| variable | y | x | b | t |

| value | 30 | 60 | 0.83333 | ? |

And it is found to be 3.8 years. The solver allows you to effortlessly play around with equations and never worry about algebra or trig or calculus.

Both general purpose solvers use Newton's Method and this technique does have limitations. Generally you won't run into issues except that some "obvious" equations can be very slow to solve.

Who has the better solver? It is kind of an equal match. Both suffer from different issues with usability. TI's is marginally more capable thanks to the extra numerical functions previously mentioned. TI will do a best attempt with sum and product series in the solver. Casio doesn't allow sums. Neither supports factorials in the solver but TI permits the product series equivalent of a factorial. TI also provides a way of bounding the search area for the solver. This can provide speedups and makes it much easier when attempting to find multiple solutions.

The previous "calculus works inside the solver" statement requires some expansion. You can say derivative(f(x)) = 0 and it will find the max/min. Neither allow for 2nd derivatives to find inflection points. (Wrapping a derivative in f() and taking the derivative of that doesn't work on the TI-30X Pro MP either.) The really impressive part of solving with integrals: you may set the limits of integration to a variable and solve for it.

Solving is a special mode in the TI-30X Pro MP. Enter "numerical solving" mode and type in both sides of the equation. This equation is saved for future use. Alternatively the f() and g() stored functions can be used in the solver too. With caveats. If f(x) = x(a+b+c) then solving for f(x) = 5 will not prompt you for the variables a b c. Instead you must use f(x) + 0abc = 5 so that the solver is made aware of the variables.

Ultimately the TI can only store 1 solver equation in permanent memory. Of course the fx-991Ex has no permanent memory. The fx-991Ex kind of stores the previous equation temporarily. The solver equations are typed into the main environment. However they disappear from the scrollback when the solver is launched. The previous equation may be recovered by pressing the left or right arrows but entering anything will wipe it. Once again the TI is better here.

In the past people have expressed distaste for the solvers in TI's graphing calculators. Originally they could only solve expressions with a single side and had an implied "= 0" for the other side. I feel this dedicated solver mode is an overreaction to those criticisms. It is far more intuitive now but far less useful because TI offers no way to load from scrollback. There isn't even an "=" symbol present in the calculator to type out both sides into the main environment. It would be tremendously useful if it could pull a single side of the equation from the history but alas. It is also not possible to move an expression from the scrollback into the f or g equations.

TI also has a really weird and stupid bug in their solver: it will return an answer for x + 1 = x Every other calculator out there will immediately say it can't be solved. The TI-30X Pro instead chews on it for a few seconds and gives a random number in the ballpark of 2E12. It has the gall to claim there is no difference between the sides too. The 12 is suspicious because that is the number of digits used for calculations. Past that and a digit of precision is lost so X + 1 will equal X out there. It might seem like a funny bug but you can never know if this is going to pop up in a less obvious way. Overall this makes TI's solver the least trustworthy that I've seen.

Specialty solvers

Both can solve complex roots of polynomials and systems of linear equations. The fx-991Ex is more powerful while the TI-30X Pro has usability features which prevent human errors and speed up work.

The Casio's power comes from its ability to handle 4th order systems. It can solve quartic equations and linear systems of 4 variables. Additionally it can solve quartic inequalities. TI can only solve cubic equations and systems of 3 variables. This is probably the biggest weakness in the TI. 4th order solvers in cheap scientific calculators isn't a recent innovation. It wasn't even pioneered by Casio. It has been used in inexpensive calculators since 2012 when the Canon F-792SGA came onto the market. The general technique goes back to 1545 and TI themselves used it in their 1989 TI-68. (However the TI-68 was not inexpensive at $150 modern day dollars.)

Casio does have 1 nice usability feature over TI: it will find the vertex of a parabola. Unfortunately it can't find local peaks or points of inflection for cubic or quartic equations. Besides it is trivial to find the vertex on either. Simply put derivative(expression) = 0 into the solver.

TI's usability features are much more significant. TI will tell you about multiple solutions. And TI gives you the option to export anything for later use. The polynomial may be saved to function memory or the roots may be saved to a variable. The "multiple solutions" part may require an example. Consider x^3 + -7x^2 + 16x -12 and its roots. It has roots at x=2, x=2, x=3. TI will tell you all of those. Casio will only tell you 2 and 3. Where is the 3rd root? Which is doubled? You have to figure out that on your own.

There is a usability oversight on the TI-30X Pro: complex solutions to polynomials rarely fit on the screen and require horizontal scrolling.

The linear system solvers both feel like they were hastily ported over from the previous generation of 2-line display calculators. Instead of using the massive amount of pixels on the screen they insist on only showing 1 variable at at time. Neither take advantage of a screen that can show multiple lines of text and forces you to page through the components of the solution.

Both calculators have a prime factoring command. Casio's is a shifted button and TI's is in a menu. Both suffer from using a small pre-computed table of primes instead of an open-ended prime search.

| model | max prime | max input | 1st error |

|---|---|---|---|

| fx-991Ex | 1013 | 1E10 - 1 | 1019^2 |

| TI-30X Pro | 997 | 1E6 - 1 | 1E6 |

The fx-991Ex also has a special mode for solving ratios but this seems pretty trivial.

"programming"

Back in the 1970s and 1980s programmable calculators were a big deal. Eventually the most common programs were turned into normal calculator functions and saved people the tedium of typing them in. (Built-ins also a lot faster and typically higher quality too. Most people don't miss programmability.) That said by 1970s standards both the fx-991Ex and the TI-30X Pro would have been considered programmable calculators.

Set your time machine for 1975. The Sinclair Scientific Programmable was just released. This was the big brother to the infamous Sinclair Scientific. The Programmable removed tangent/arcsin/arccos in exchange for the ability to create a single program of 24 opcodes. However in reading the manual you'll notice something missing: there is no branch instruction. Instead all of the programs are simple algebraic expressions. It is "programmable" but it isn't Turing complete. People loved it anyway. They were willing to pay $80 for it when it launched. That is $450 in 2022 dollars. This sets the bar for what I am willing to consider programmable: a way of conveniently automating the process of "plug and chug" formula crunching.

By these standards the fx-991Ex is massively programmable and the TI-30X Pro is reasonably programmable.

These days every calculator will provide some automation. The simplest is that the last calculation can be performed again by pressing "equals" repeatedly. Maybe in school you entertained yourself by typing in "+ 1" and repeatedly pressing equals to see how far you'd go before getting even more bored. That same trick can be used with more complicated expressions. (Incidentally it is also considered a program! See page 14 of the Sinclair Programmable Library (PDF) for the Tally Counter program.)

TI provides a slight upgrade to that called "Stored Operations." It allows for the creation of a simple macro that you can play back in the editing environment. It also displays a running count of how many times it was iterated. Unfortunately it is dumb as sack of bricks. The examples show that you might have to do things like "sqrt ( number macro" to use it. In other words you need to manually type any opening functions or parenthesis. Ed Shore has some examples showing it in action. I was unable to find any more impressive examples. Casio has no similar feature and good riddance.

The most advanced programmable feature in the TI-30X Pro is the Expression Evaluator. But let's detour through Casio's version of it.

CALC was introduced by Casio in 1998 with the fx-85W as a refinement that greatly simplified elementary programming. You enter an algebraic expression with variables and hit CALC. It will then prompt you for variables and gives you the option to re-use the previous value instead of retyping it. Finally it shows the result and loops around for you to do the same calculation again. In 2000 with the fx-100MS Casio added the revolutionary ":" symbol. This lets CALC handle multiple expressions simultaneously while reusing the same variables. For example if you want to find the surface area and volume of a bunch of spheres: 4*pi*r^2 : (4/3)*pi*r^3 After hitting CALC you need only enter the radius once and it gives you both results. Then you can batch process an entire list of numbers. Ed Shore has a good tutorial explaining more and Nayuki has some remarkable examples for the previous generation of Casios. After this it spread to the other low-cost scientifics. Some call it ALG instead. (It is worth noting that the idea of CALC long predated Casio's version of it. The venerable 1989 TI-68 had something very similar.)

Being able to execute multiple statements and even store intermediate values makes the CALC feature better than much of what was available in the 70s and 80s. (Many of them didn't let you read or edit programs. You blindly typed them in.) Unfortunately the usability has slipped a little in the fx-991Ex. Storing a variable automatically runs the expression. This saves you a keystroke in normal use but makes multi-expressions more tedious to construct. An improvement would be to keep the old behavior if there is a ":" already on the line. For complicated multi-expressions you might be better off using Casio's spreadsheet.

How does TI's Expression Evaluator compare? It is terrible and extremely limited compared to what Casio had 20 years ago. It is the "expr-eval" button on their calculators. To their credit that is a more descriptive and friendly name. But I can't say anything else nice about it.

- Can't do multiple simultaneous expressions.

- Can assign a useless temporary variable but stupidly prompts you to give a value to that variable.

- Doesn't automatically loop.

- Requires far more keystrokes for everything.

There is no equivalent of the ":" symbol. The comma could fill that role but TI didn't think of that. Crunching multiple expressions requires either entering the equations multiple times to reuse the values or entering the values multiple times to reuse the equations. Complex numbers can be abused to perform 2 limited operations independently but this is very error prone.

After evaluating an expression Casio will loop back and let you enter new variables. This continues until you break out. TI returns to the main editing environment. You then need to again hit "expr-eval" (a shifted command) and press enter to reuse the previous expression. 3 keystrokes to Casio's none.

Both calculators correctly handle non-algebraic functions such as an integral in the expression. Though they both uselessly prompt you to enter a value for the integrated variable.

Both calculators allow for expressions to be drawn from the editing history. But TI requires 2x as many keystrokes to scroll back since the history gives access to inputs and results for each time that "expr-eval" was run. Casio's history goes through only the expressions and not the results. Making it 2x faster to dig through.

TI does provide another mechanism for crunching expressions via lists under the "data" mode. But these aren't comparable because you may only do 2 functions of 1 variable or 1 function of 2 variables. Any variables used in "data" mode are more like named constants.

However TI-30X Pro MP does have a nice programming feature the fx-991Ex lacks: function memory. If you want to add a gamma function to the calculator you can. But there are only 2 function slots so you can't have a library.

Regressions

Regressions are my 2nd favorite feature after the solver. They turn a bunch of messy real-world data points into a crisp and clean equation. Both calculators can do regressions as part of their statistics suites. However there is a clear winner here. TI utterly crushes Casio when it comes to both capabilities and usability.

The Casio can hold 160 single-value datums or 80 XY pairs or 53 XYZ triples of data. The TI-30X Pro MP only holds 50 of any. Casio wins? Not at all. Casio could hold 1000 triples and the TI would still be better. The fx-991Ex will forget all of them after a few minutes or when you need to do something other than statistics. The TI-30X Pro remembers them forever. I never really wanted to use Casio for bigger problems because all the data I entered will vanish. Often field work requires either waiting an hour to get another reading or traveling between multiple stations. With the Casio you'd need to keep a paper record and avoid doing the regression until the end of the day. With the TI you can use the calculator to record data and make some early estimates as you go.

50 points is also more than enough. Most of the time you'll be using regressions to find coefficients for low-noise systems that you know have a clear relationship. The rule of thumb in those situations is to have 7 data points. More than 20 and you should probably be using a computer.

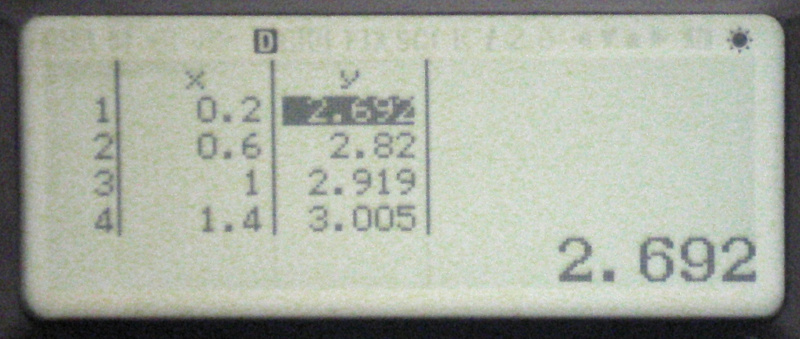

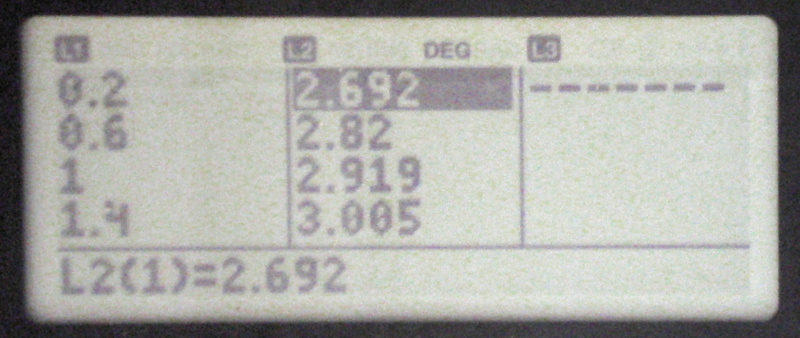

The TI-30X Pro uses a column-major style of data entry. X values go down a list. Y values go down another. Frequency or weight goes down the final list. The lists aren't hardwired either. You can select any list to be any set of values. In other words it is trivially easy to swap the X and Y variables. I do this regularly to check to see if the coefficients are cleaner. (Swapping variables like this will also turn the quadratic regression into a bonus square root regression.)

The fx-991Ex uses row-major tuples to represent data. It can't do any of the previously mentioned things. Enabling frequency will delete all of the old data.

Both calculators offer many regression equations with a slight edge to TI: TI can do cubic regressions. Though I don't really care for this feature. Cubic curves don't show up that often in real systems. Furthermore they are of limited use. Since they are "curvier" they can often find a better and closer fit than other equations. However they are less useful for extrapolation because they tend to explode outside of the range of the given data points. Overfit the data and the curve beyond the data suffers.

The TI-30X Pro can automatically export the regression to formula memory. The exported function will spell out the coefficients instead of using a/b/c/d. This means you can store 2 different regressions in the 2 formula memories and still have all of the variables free for your own uses. Casio stores the coefficients to variables and makes you re-type the equation if you want to do anything with the regression.

Probability distributions

Both calculators provide access to the same 7 distributions: normal PMF/CDF, inverse normal, binomial PMF/CDF, poisson PMF/CDF. Casio's UI is unexpectedly weak here. You can't select from the 7 directly since each page starts over from 1. TI lets you go straight in. Casio makes switching between distributions cumbersome. TI lets you tap the up arrow a few times to return to the selection menu. Both have very similar entry systems for single-shot calculations. TI's input fields have better and more descriptive labels. Both let you do arithmetic inside the entry fields. Both let you export single-shot results to a variable. TI makes the process more obvious by making you choose a variable. Casio expects you to know that the STO command works on the result. Both allow batch processing with lists. Surprisingly Casio doesn't nuke the list of x values when switching between binomial and poisson calculations. But its still not as good as TI's list system. TI has an extra feature: it can automatically populate a distribution list with a range. Overall TI is the clear winner.

"List processing" differences

This almost feels like an apples to oranges comparison because of how far Casio has pushed the state of the art versus how practical TI's implementation is.

Casio has managed to pack an entire spreadsheet app into the fx-991Ex. It does everything a full sized spreadsheet can do but does rely heavily on menus to access those features. You've pretty much got every calculator function available too. Even integrals and derivatives! Though filling a table with integrals will slow the sheet down to a crawl. Unfortunately the spreadsheet is a gimmick because everything is lost when the calculator powers off. This is particularly frustrating considering the matrix memory is preserved.

It should go without saying that there is no way to move stuff between modes on the fx-991Ex. Wiping the memory sees to that. It would be nice to move numbers between matrices and the spreadsheet or between the spreadsheet and statistics.

TI opted to go for for something less powerful but more flexible: lists. These lists were used in the TI-36X Pro for doing regressions but in the TI-30X Pro MP they have been extended to allow you to fill the lists with functions. Accessing this feature is not obvious: press the "data" button 2 times. You may assign a formula to a list and that formula pulls from values in another list. There are also options to sort a list or to sum up the list and save the result to a variable. In short you have basic spreadsheet functions available that can only operate on the level of an entire column. And there are only 3 columns so it feels a little constrained.

Using these lists for regressions and list processing works very well in conjunction. Let's say you start putting in some time-series data pairs. Time goes into L1 and the measurement goes into L2. But the time you entered was the clock time. For the sake of the regression it would be more convenient if the 1st entry started at 0 hours instead of 9 o'clock. It isn't necessary to re-enter all the data. Simply do L3 = L1 - 9 and then perform the regression again between L3 (adjusted time) and L2 (measurements).

A list with an equation is automatically updated when data is added or changed. Of course circular references are not allowed. TI did think of this however. When clearing an equation from a list the calculator will convert all of the elements into numerical values. This allows for bouncing back and forth between 2 lists to perform multiple-step processes.

My favorite combination of regressions and lists is to calculate the relative error. Do a regression and export the function to f(). Then set L3 = 100(f(L1) - L2) / L2 to see the percent error at each of the original data points.

Table mode

Table mode is the text-based alternative to graphing. Supply some equations and the calculator will generate a series of Y values from X inputs. In some ways it is superior to graphing:

- Y axis auto ranges

- Can read off exact values

- Can input exact values

- Faster

The primary downside is that it becomes easier to overlook asymptotes and discontinuities.

Both the TI-30X Pro MP and the fx-991Ex have pretty similar table modes. Both only allow for 2 functions. Both have mechanisms for generating points along an interval or manually entering values. Neither provide for any way to move data between the table and statistics.

Casio asks for a range and a step size. If you want more points you must re-enter the range. TI just asks for a starting point and step size. Scrolling generates more rows on the fly. TI is better here.

Casio lets you manually enter (or edit) inputs at any time. And the massive memory will hold a bunch of values for the session. TI instead requires that you enter a special manual entry table mode and then only gives you 3 rows to manipulate. Casio is better here.

Casio's is also generally nicer to look at because of sharper fonts. However TI is better overall because the functions are saved and incorporated across everything that the calculator can do.

Integrator differences

Both calculators have fast and accurate numerical integrators. This is primarily due to the use of the Gauss-Kronrod formula. Many calculators instead use the much more primitive Simpson's Rule. (If a calculator allows you to set the number of intervals then it is probably using Simpson's.) The Gauss-Kronrod algorithm only has 1 factor to tune: the epsilon for when the error is low enough. Both calculators use the same epsilon for their integrators: 1E-5. From this you would expect them to have nearly identical performance characteristics. They don't. Instead Casio's integrator is more accurate and TI's integrator is more flexible.

The TI-30X Pro MP allows for a much wider variety of functions to be integrated. Sums and products may be used in integration. (This generates and error on the fx-991Ex.) Discontinuous functions like integer-part and fraction-part may be used inside TI's integrator as well. Neither permit factorials but TI can fake it with a product. TI will error if you try to use random numbers in an integral but there is a way around this: wrap the rand call with the f() function and integrate that. It is useless for this specific example but its a handy trick to remember.

Neither calculator will integrate across singularities. The TI-30X Pro MP will however allow the integration to start/end at a singularity. This suggests TI is using a variation of GK (PDF) which doesn't sample the endpoints. Assuming the area is finite the TI will eventually find the result. "Eventually" is a key word though. It is often faster and surprisingly more accurate to slightly offset the limit. But this isn't consistent across all class of equations.

Many people are concerned about the speed or accuracy of a numerical integrator. However I feel there is something more important: where does the integrator return completely wrong answers? There is an entire class of equations that seems to break every numerical integrator I've ever tried it with: inverse squares. The inverse square law appears everywhere in physics and integrating over it is common. It is also common to want to integrate "to infinity" in order to find the maximum effect on something moving through an inverse square field. For example when calculating escape velocity. Of course a scientific calculator has no concept of infinity so instead the standard practice is to approximate with "a really big number." But integrating inverse squares over moderate large distances will break.

Consider the equation f(x) = x^-2 for these tests. It is a textbook example of a curve of infinite length but finite area. The area under the curve from 1 to infinity is exactly 1. At "very large distances" it will be a hair less than 1. Let's try integrating to various limits:

| int(x^-2, 1, A) | A=1E5 | A=1E10 | A=1E15 | A=1E70 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| fx-991Ex | 0.99999 | 0.9999999999 | 6.98E-13 | 0 |

| TI-30X Pro MP | 0.99999 | 7E-8 | 6.98E-13 | 0 |

| int(x^-2, 1, A) | breaks at A=? | type of error |

|---|---|---|

| fx-991Ex | 5.9E12 | near zero |

| TI-30X Pro MP | 5.9E7 | near zero |

In some fields it is plausible to exceed these without even trying. The distance between the Sun and Mercury is 5.8E10 meters. In atomic physics 1 meter is 1.89E10 bohrs. 1E8 seconds is 3.2 years. Calculators using Simpson's Rule might start producing wrong answers in the 100s or 1000s.

Exponential decay is another similar class of equations. You might want to integrate to infinity to calculate the mean lifetime. Where do those break? The area under the curve f(x) = e^-x between 0 and infinity equals 1 but these calculators begin returning very low numbers (or zero) surprisingly early.

| int(e^-x, 0, A) | breaks at A=? | type of error |

|---|---|---|

| fx-991Ex | 6395 | near zero |

| TI-30X Pro MP | 3564 | near zero |

It is also surprising how things break when the lower limit is different. For example int(e^-x, 1, 3314) generates a wrong answer on the TI and the range (1, 6153) is wrong on the Casio. I didn't expect the upper limit to decrease. Normally solving an integral as the sum of multiple smaller segments is more accurate.

I am curious how far your calculator can go and would like to add more to these tables. The Casio fx-9750GIII graphing calculator performed identically to the fx-991Ex. Nice to see that Casio doesn't hold back their scientific calculators like TI does.

Display and UI Differences

Superficially these use very similar LCDs. Both are reflective dot matrix displays of nearly identical size. The Casio is 192x63 and the TI is 192x64 pixels. But overall the Casio has a nicer screen that appears crisper and a little brighter. However TI uses their screen more effectively. Both because of how menus work and font choices.

The menu design is another major difference in philosophy. The fx-991Ex uses a lot of multi-level menus that can be quickly navigated entirely with numbers. The TI-30X Pro MP avoids multi-level menus. Instead the menu options are shown in place of the menu name and when multiple levels are used they are depicted as tabs.

As an example consider choosing degrees or radians. On the fx-991Ex you press "setup" and then see "2: Angle Unit." Pressing that then lets you hit 1/2/3 for deg/rad/grad. The D pad is never used. On the TI-30X Pro you press "mode" and are immediately presented with a line that says "degree radian gradian" with the current setting highlighted. Tap left or right to choose and press enter to select.

Being able to see all of the settings and all possible options up front is very convenient. When you press "mode" on the TI you are presented with a lot of information. Just navigating to the same information on the Casio requires 10 keystrokes. And then the Casio still doesn't tell you what any of the settings are.

That said.... the menus on the TI-30X Pro are rough in places. There is no consistency between them. It feels like there was never a shared library or design document involved and every engineer just kind of did their own menu. Things are pretty inconsistent even inside a single menu. Take conversions for example. Pressing "convert" will bring up a list of numbered categories. The list can be scrolled up/down with the directional pad and the scrolling is indicated by arrows on the left edge. At the top or bottom pressing up/down will wrap around. Left returns you to the top of the list. Right also returns you to the top of the list instead of jumping to the bottom or entering a category. This menu may be exited with "quit" or "clear." A category is selected by either pressing its number or highlighting it and pressing "enter." Once inside a category there is an entirely different set of rules. Numbers may not be used for any selection. The directional pad moves the selection around a 2D grid of conversions. Arrows are still used to indicate scrolling but now they are on the right edge. At the edges it does not wrap. "Quit" will still exit but "clear" does nothing. Most surprisingly pressing "up" while on the topmost line will exit this submenu and returns to the category selection. Some menus will remain open through the sleep shutdown. The conversion menu and submenu will both stay in the menu and even retains the position of the cursor across a power cycle. Other menus instead quit and return to the main environment.

Constants are more user friendly on the TI. It will show the symbol and the full name and the units. Casio only gives you the symbol. But Casio's entry system is faster with any constant only requiring 2 keystrokes to access and are all bound to numbers for touch typing.

Casio blanks the screen when it is thinking hard. The degree/radian annunciator might be the only indication that the calculator is on. TI has a "busy" icon and leaves the screen visible so that you can (usually) see what problem it is solving.

The full dot matrix display is impressive but could be used better. Casio tries to show off their resolution by using a serif font. It doesn't help readability and makes everything look messy. Overall the displays don't use space very efficiently because of fixed width fonts. The full width decimal point and full width exponents add a lot of bulk to every number shown.

The display fonts also feel out of place with the keypad printing. Everything on Casio's keypad is sans serif while the display is serif. TI's sans serif display looks cleaner even though their fonts are chunkier. However TI makes a font sin of their own: the number pad has a barred 7 and unbarred 0. While the display has a barred 0 and unbarred 7. Madness!

Physical Differences

Some basic physical information. I've included some info for the fx-9750GIII graphing calculator because the power consumption numbers are pretty eye-watering.

| model | battery | panel size | auto off | weight | size | volume |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fx-991Ex | 1x LR44 (0.19Wh) | 4.5 cm^2 | 10 minutes | 133g | 168 x 82 x 18mm | 248 cc |

| TI-30X Pro MP | 2x CR2032 (1.2Wh) | 7.6 cm^2 | 3 minutes | 132g | 171 (184) x 80 x 16mm | 219 cc |

| fx-9750GIII | 4x AAA (3.9Wh) | 10 or 60 minutes | 238g | 180 x 87 x 24mm | 375 cc |

I didn't count the weird little latches in the volume of the TI. Some of my own measurements for power consumption:

| model | off | idle | crunching | idle solar | full solar |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| fx-991Ex | 0uW? | 39uW | 345uW | 450 lux | 1200 lux |

| TI-30X Pro MP | 0.9uW | 750uW | 2970uW | 1000 lux | 2000 lux |

| fx-9750GIII | 192uW | 1540uW | 150mW |

I'm sure the Casio was using some power while off to retain the variables in memory but it was too low to measure. The idle power is also dependent on the LCD contrast. Hats off to Casio for making a calculator that uses 64% less power at full speed than Texas Instruments uses at idle! While being clocked 37% faster. I don't know if it is the silicon or the programming but cycle for cycle Casio is 19x more efficient at idle and 13x more efficient while processing.

The lux numbers are the minimum level of indoor illumination so that the calculator can either be idle or perform heavy calculations entirely on solar power without blacking out. Nearly any little amount helps to extend normal battery life. The TI's behavior changed slightly under solar power: it would blank the screen while crunching. Be aware that the TI-30X Pro MP will often only turn on after a hard reset (on-clear button combo) if the batteries are removed. I don't recommend trying to run the TI on solar.

Finally some extrapolated values for battery life:

| model | off | idle | crunching |

|---|---|---|---|

| fx-991Ex | ∞ | 6.7 months | 3.2 weeks |

| TI-30X Pro MP | 150 years | 2.2 months | 2.4 weeks |

| fx-9750GIII | 2.3 years | 3.5 months | 26 hours |

The idle runtimes for the solar calculators might be misleading. With the cover off they can usually sustain themselves entirely from poor lighting.

The LR44 costs about $0.50 each while a pair of CR2032 is about $2. Either way the running costs are pretty low.

My TI was made in the Philippines and both Casios were made in Thailand.

Ergonomics

The Casio is far nicer to hold in the hand. It is all curves and bevels. The TI's design can best be described as "flat." The Casio has no rubber bumpers and instead has small molded plastic nubs for stability. The TI has 12 rubber bumpers. This includes 4 bumpers on the inside of the cover to keep from marring the face of the calculator when closed. Based on past experiences with TI's calculators I expect all 12 to fall out sooner rather than later if the calculator is carried regularly. But after 1 year of use and carry they are still all in place.

The keypad on both is fine. The TI has slightly stiffer buttons which require 80 grams-force to the Casio's 50 grams-force to actuate. The "flatness" and "curve" themes of the body carry over into the keys. TI has completely flat keys and only 3 different key caps. Casio uses a variety of flat/concave/convex/rounded keys: 8 in all. (Not counting the D pad for either calculator.) Casio also managed to put a slight curve into the face of the keyboard itself. It is subtle and only subtends about 1.5 degrees of an arc.

Casio places the EE in the number pad and the negative key with the scientific functions. TI does the opposite. Their negative is in the number pad while the EE is with the functions. Both have reasonable keyboard layouts. TI makes the unusual choice to have answer and square root and invert be shifted keys. Both hide many functions inside menus. TI at least has the excuse that the keyboard is full. Casio left 6 keys unshifted and that could have removed an entire menu. Not to mention the 26 keys without an Alpha use. (5 of the 14 alpha keys aren't even letters. They could have put a few more commands in there.)

All of TI's printed labels are far easier to read. A few of Casio's (the blue text on the black background) are difficult to make out under poor light. If you are color blind do not even bother getting the Casio. In part this is because TI's keypad is much simpler. TI only uses 1 shift key and no keys change function with mode. The TI ends up being nearly monochromatic. While Casio's permutations mean that some keys have 4 functions and just as many labels. TI does occasionally put that many functions onto some keys but simply omits the labels to keep things looking simple. Eg the "sin" key is actually sin/arcsin/sinh/arcsinh while not mentioning the hyperbolics.

The downside to TI's cleaner layout is that there is less stuff accessible from the keypad. These operations are on Casio's keypad but require extra keypresses on the TI: sum, cube root, cube, base 10, base 16, base 2, base 8, DMS, factorize, complex angle, complex i, absolute value, M+, M-, polar/rect conversion, random, random int, round.

There are a few things on TI's keyboard that aren't on Casio's: the 6 hyperbolic trig functions, contrast adjustment.

It feels like TI has wasted several buttons. "On" can only turn on the calculator or interrupt a long computation. It could be used to quit from menus and thus remove the dedicated "quit" button. "Op" and "set op" are both completely useless. And maybe this would be controversial but the _/_ and _ _/_ fraction keys could be multitap instead. In total freeing up 4 spaces.

Both calculators have a space in their case to hold a card. Casio's is nearly useless. It can only fit a small card of 71mm by 49mm. It doesn't fit very nicely either since the card grooves aren't symmetric and the inside of the case is slightly concave. This also makes taking notes on the card more difficult.

TI on the other hand can fit almost an entire 3x5 index card in its cover. Trimming it to 67mm tall is a perfect fit and several can be stashed there. The TI's cover is nearly flat and open on the sides. Overall it is perfectly suited for impromptu scribblings or small sketches and has replaced my field notebook. My initial impression was that TI's cover looked weird and cheap but with the addition of index cards it has become one of my favorite things about this calculator. Those weird tabs on the case ended up being nice too: it makes the calculator easy to distinguish by feel in the bottom of a bag.

Conclusion

So here we are. Overall I recommend the TI-30X Pro MathPrint unless you absolutely need the fx-991Ex's 4th order capabilities or its superior CALC/spreadsheet modes or want to power the calculator solar-only.

I really want to prefer Casio's products. The Casio is an engineering marvel given its speed and power consumption. TI is doing shady stuff by withholding this model from the US market. And Casio is more serious about language localization. Do you know how hard it is to find calculators that support right-to-left arabic script? The Casio fx-991Ex AR has that.

But my goodness is it ever nice that the calculator remembers what you are doing. At the very least Casio should remove the 10 minute timer and let the fx-991Ex run forever if there is enough power from the solar panel. A mode flag to disable the timer entirely would be even better. Neither of these require major changes to the firmware and would make it become an even tossup between these 2 models. (The calculator would still wipe the memory on mode changes since that would require extensive firmware changes.) But knowing Casio they'll instead add something revolutionary like a CAS to their next scientific instead of improving the memory.

If you really want Casio's spreadsheet feature and memory then there is the Casio FX-9750GIII graphing calculator. There is a 3rd party CAS available for it. Python is included. And it can be overclocked. How does Casio's entry level graphing calculator compare to their top of the line scientific? Well let me write another 10k words.... just kidding. Here is a very quick rundown:

- Cost: MSRP is 3x higher. Sometimes on sale for only 2x higher.

- Size: 50% bigger and 80% heavier

- Display: 128x64 (47% less pixels but 1 extra line of text)

- Speed: Sometimes 30% faster. Sometimes 6x faster.

- Power consumption: 40x more when idle. 400x more when crunching.

For the Americans who are thinking of the TI-36X Pro: importing the european version is worth it. Here is a summary of the TI-36X Pro issues when compared to the TI-30X Pro:

- 2x slower

- Missing the pseudo-spreadsheet capabilities

- No way to choose the integrator's epsilon

- Encourages TI to keep selling 11 year old calculators

- U G L Y

If you are interested in buying these there are a couple of purchase links here. Be aware that a few of those links are amazon affiliate URLs if you don't like that sort of thing. None of the european TI-30X Pro links are affiliated though because I am not good at affiliating.

Importing the TI-30X is easiest via european Amazon. Every regional distributor has different prices and availability so I've linked all of them. Shipping will usually be $15-$20 to the US. And there will be a $2 currency conversion fee tacked on too. You might be able to find it for $10 less as a warehouse deal.

- Casio fx-991Ex ClassWiz

- Entry level Casio fx-260 Solar II

- Graphing Casio fx-9750GIII

- Replace the Casio's alkaline LR44 with a silver oxide SR44 before it leaks

- TI-30X Pro at amazon.co.uk

- TI-30X Pro at amazon.de

- TI-30X Pro at amazon.es

- TI-30X Pro at amazon.fr (usually has the best price)

- TI-30X Pro at amazon.it

- TI-30X Pro at amazon.se

- Spare CR2032 for the TI

Be careful not to confuse the Pro version with the Plus version. The Plus is stripped of a few features to make it more friendly to certain schools.

If there is anything you'd like me to add or expand on in this review please post comments here.

I've tried to cite sources wherever possible but many broad observations were only formed by simply looking at a lot of calculators. These databases were invaluable and worth digging into if you are generally curious about the history of technology.

- RSKey (Includes a sample Gamma Function program for every calculator in their collection.)

- Datamath

- Ledudu

- Museum of Soviet Calculators

- Calculator.org

- HP Museum

- Voidware

- Arithmomuseum

- Vintage Calculators (Also has a great history article.)

- MyCalcDB

- Old Calculator Museum

- Casio Calculator Collectors

- Torensma

- Calcuseum